Iván Moratilla Pérez (a), Esther Gallego García (b) y Francisco Javier Moreno Martínez (c)

(a) Asociación de familiares de personas con Alzheimer de Arganda del Rey, Madrid, España

(b) Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad de Jaén, España

(c) Dept. de Psicología Básica I, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, España

(cc) Iván Moratilla.

Humanity and Art make an indissoluble marriage, it is impossible to comprehend one without the other. Even before producing the first musical instrument, humanity already sang; before using a canvas, humans painted on the walls of a cave. Creative manifestations invariably take place in “poverty and wealth”, but also in “sickness and health”. In this article we introduce the reader to the subject of art and dementia, highlighting the creative potential of patients, and including examples of educational programmes that some museums develop for people with this condition.

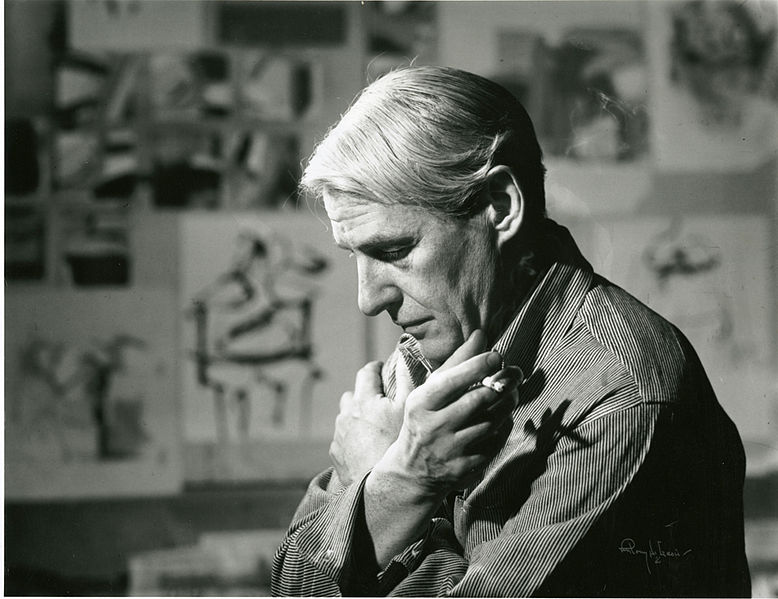

Willem de Kooning, a leading figure of abstract expressionism, was awarded in 1986 with the National Medal of Arts of the US Congress: the highest honour granted to an artist in the American country. He was 82 years old. A short time before, he had completed several works. In fact, he painted 254 between 1981 and 1986, a very striking figure, particularly if we take into account that, in his maturity, finishing some of his works could take him more than a year. At 78, the Dutch painter’s technique had evolved. Clear backgrounds and primary colours, sinuous forms that baffle the viewer. The brush strokes move rhythmically, the artist is pure action in front of the easel. His new art is fertile, noisy, full of life. His diagnosis at that age: Alzheimer’s disease.

Figure 1.- Willem de Kooning in his study. (dp) Smithsonian Institution Archives. Image # SIA2011-2241.

The case of Willem de Kooning does not represent an isolated phenomenon. According to Zaidel (2014), some artists with Alzheimer’s disease, or other types of dementia, continue to produce art despite the neurodegenerative disorder they suffer, without a reduction in their artistic expressions. Regardless of the changes in the complexity of their productions, their creative behaviour is not usually diminished until the motor deterioration is so severe as to significantly compromise their manual dexterity.

Even more interesting is noting how some people with dementia, without previous creative achievements, spontaneously begin to exhibit artistic behaviours after the syndrome’s onset (Chakravarty, 2001; Miller and Miller, 2013; Viskontas and Miller, 2013). This circumstance may occur when the dominant cerebral hemisphere typically the left hemisphere deteriorates and, as a consequence, its control over the right hemisphere presumably more creative fades away. This “paradoxical functional facilitation”, by virtue of which creativity or artistic interests flourish in some people with dementia, is not at all unknown to scientific research (Kapur et al., 2013).

As a matter of fact, there is empirical evidence of the creative potential of patients with dementia. In a recent experiment 122 art experts were asked to determine, based on criteria such as style and composition, whether the images shown to them belonged to creations by professional artists or if, contrarily, they were made by individuals without previous artistic experience. The experts, who were unaware that half of the works belonged to people with dementia, attributed a significant number of works of patients to creations by professional artists (Belver and Ullán, 2017).

Undoubtedly, aesthetic enjoyment may also be present in the absence of artistic production. The truth is that the relationship with art covers a broad spectrum, ranging from active behaviours (creation) to passive behaviours (contemplation). Art is for everyone; there is no reason to restrict its potential benefits to an elite or a limited group. As article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states, “everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community and to enjoy the arts”. Under this premise, the XIII General Assembly of the International Council of Museums proposed, more than three decades ago, that museums’ educational and accessibility projects should consider all people, regardless of their (dis)ability. This initiative has been followed, gradually it may be, but still surely, giving rise to a multiplicity of educational programmes aimed at audiences with specific learning and communication needs.

Using a non-pharmacological approach, several museums and art centres contribute nowadays to stimulating the cognitive and affective abilities of people with dementia, while preventing their isolation and social exclusion. Let’s see some examples:

The Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA), through its “Meet Me at MoMA” programme, organizes visits for patients and their caregivers. A special interest is put in the interactions with the participants, using body language and speaking clearly. The museum seeks to establish an empathetic connection and share vital experiences. Its fundamental goal consists of contemplating, debating or creating art, in order to convert it into a means of individual expression.

The Museum of Fine Arts in Murcia (MuBAM) organizes cultural and social programmes aimed at people with dementia and their relatives. In addition to visits to the museum’s collection, outings are arranged to the monumental complex of San Juan de Dios. Some of the techniques used by the organizers include cognitive, reminiscent and emotional strategies. In one of the museum’s proposals the participants are encouraged to create a “memories suitcase”, keeping in it objects that commemorate representative events of their past.

The Prado National Museum has developed several educational projects over the years. Its cultural heritage is the instrument and the main motivator to nurture interest in art and knowledge. Educators stimulate the memory and attention of patients enriching activities with visual, fragant, tactile and musical stimuli. In addition, reminiscence dynamics are carried out in which dialogue takes place through verbal and body language. The production of artistic works is also promoted and, during 2016, two public exhibitions were organized in Madrid with creations of the patients themselves (Moratilla-Pérez and de Frutos-González, 2017).

Dementia is commonly treated with theraphy and medication. Prevention methods and vaccines are being investigated. The effective management of the syndrome is the horizon towards which we trace our route. However, we do not know how much time we will spend going over that path. Meanwhile, it is worth remembering that the brain deals with sensory stimuli and that the arts offer exceptional means of expression and aesthetic enjoyment. What we have heard, seen or felt gives shape to our unique and distinct individuality. In this manner, a melody, a landscape, or the combination of a wealth of colours manage to reach that part of the self where identity dwells; perhaps the hardest part to forget.

References

Belver, M.H. & Ullán, A.M. (2017). Artistic creativity and dementia. A study of assessment by experts. Arte, individuo y sociedad, 29 (Núm. Especial), 127-138.

Chakravarty, A. (2011). De novo development of artistic creativity in Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology, 14, pp. 291-294.

Kapur, N., Cole, J., Manly, T., Viskontas, I., Ninteman, A., Hasher, L. & Pascual-Leone, A. (2013). Positive clinical neuroscience: explorations in positive neurology. Neuroscientist, 19, 354-369.

Miller, Z.A. & Miller, B.L. (2013). Artistic creativity and dementia. Progress in Brain Research, 204, pp. 99-112.

Moratilla-Pérez, I. & de Frutos-González, E. (2017). La persona con demencia y el Museo Nacional del Prado: el arte de recordar. Arte, Individuo y Sociedad, 29 (Núm. Especial), 25-43.

Viskontas, I.V. & Miller, B.L. (2013). «Art and dementia: how degeneration of some brain regions can lead to new creative impulses». In: Neuroscience of Creativity, eds. A.S. Bristol, O. Vartanian y A.B. Kaufman (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press), pp. 115-132.

Zaidel, D.W. (2014). Creativity, brain, and art: biological and neurological considerations. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8:389. doi: 10.3389/ fnhum.2014.00389

Received on January 5th, 2018.

Accepted on February 2nd, 2018.

This is the English version of Moratilla Pérez, I., Gallego García, E., y Moreno Martínez, F. J. (2018). Arte inolvidable. Ciencia Cognitiva, 12:2, 24-26.