Pamela Barone (a,b), Guido Corradi (b,c) y Antoni Gomila (a,b)

(a) Dept. de Psicología, Universidad de las Islas Baleares, España

(b) Grupo de Evolución y Cognición Humana (EvoCog), UIB, IFISC, Unidad asociada a CSIC, España

(c) Dept. de Psicología, Facultad de Educación y Salud, Universidad Camilo José Cela, España

(dp) Pixabay.

Children’s capacity to understand other people’s false beliefs is commonly tested in tasks in which children must predict the behavior of a person who has wrong information about an event. The results of new, non-verbal false belief tasks have led several researchers to conclude that false belief attribution appears during the second year of life. However, the available evidence is still inconclusive. In the present article, we show the findings of the first meta-analysis of all non-verbal false belief tasks. Results indicate that 2-year-old children might attribute false beliefs, but they also reveal a high heterogeneity in the effects and possible publication biases.

In everyday social interactions we attribute mental states (e.g., beliefs, desires, and intentions) to other people in order to predict or explain their behavior. For example, if you know that John wants to drink juice, and you know that John believes that the juice is in the fridge, you can predict that he will search for the juice in the fridge. This ability to impute mental states to others (and also to oneself) to make predictions about the future behavior of other agents is called theory of mind (Premack & Woodruff, 1978).

Developmental psychologists have designed the false belief task to study when theory of mind emerges (Baron-Cohen, Leslie & Frith, 1985). In the false belief task, the child is shown a puppet named Sally who puts an object in a basket. While Sally is absent, another puppet appears and transfers the object from the basket to a box. Upon Sally’s return, the child is asked: “Where will Sally look for the object?” By the age of 4, children consistently pass the task and reply that Sally will search for her object into the basket, where she (wrongly) believes it to be (Wellman, Cross, & Watson, 2001). Correct performance on the false belief task has been established as proof that someone has a theory of mind, because she is able to realize that an agent with a false belief holds an informational state which is incongruent with reality.

More recently, however, the results of a new set of simpler, non-verbal false belief tasks have led some researchers to claim that the attribution of false beliefs appears in the second year of life (see Scott & Baillargeon, 2017, for a review). These new experimental paradigms involve implicit and spontaneous measures such as “violation of expectation” (Do infants look longer when Sally looks for her object where it really is?), “anticipatory looking” (Do infants look first at the location where Sally will search for her object?) and “interactive responses” (Do they help Sally to search for her object or do they point to a location taking her belief into account?). However, 15 years after the first ground-breaking study, there is no consensus yet about the capacities displayed by infants in the non-verbal tasks, and some studies could not replicate the original finding (Kulke & Rakoczy, 2018). For that reason, we carried out the first meta-analysis of the results from non-verbal false belief tasks in infants younger than 2 years (Barone, Corradi, & Gomila, 2019).

The final selection of studies amounted to 56 situations in which the capacity to attribute a false belief to another person was examined. A total of 1469 infants with a mean age of 19.55 months were tested. When the whole available data were analyzed together, results showed that infants performed these tasks above chance level, that is, they recognized that other person’s mind can hold a belief incongruent with reality. However, we also found that results varied strongly from study to study, much more than it would be expected by chance, suggesting that other unknown factors modulate the effect. Part of this variability is explained by the type of paradigm employed. In general, infants’ correct performance was more likely in the violation-of-expectation paradigm. Finally, we found a possible publication bias in this body of work: Some studies with nonsignificant results were probably not published or were re-analyzed and the analyses with significant result were preferentially published.

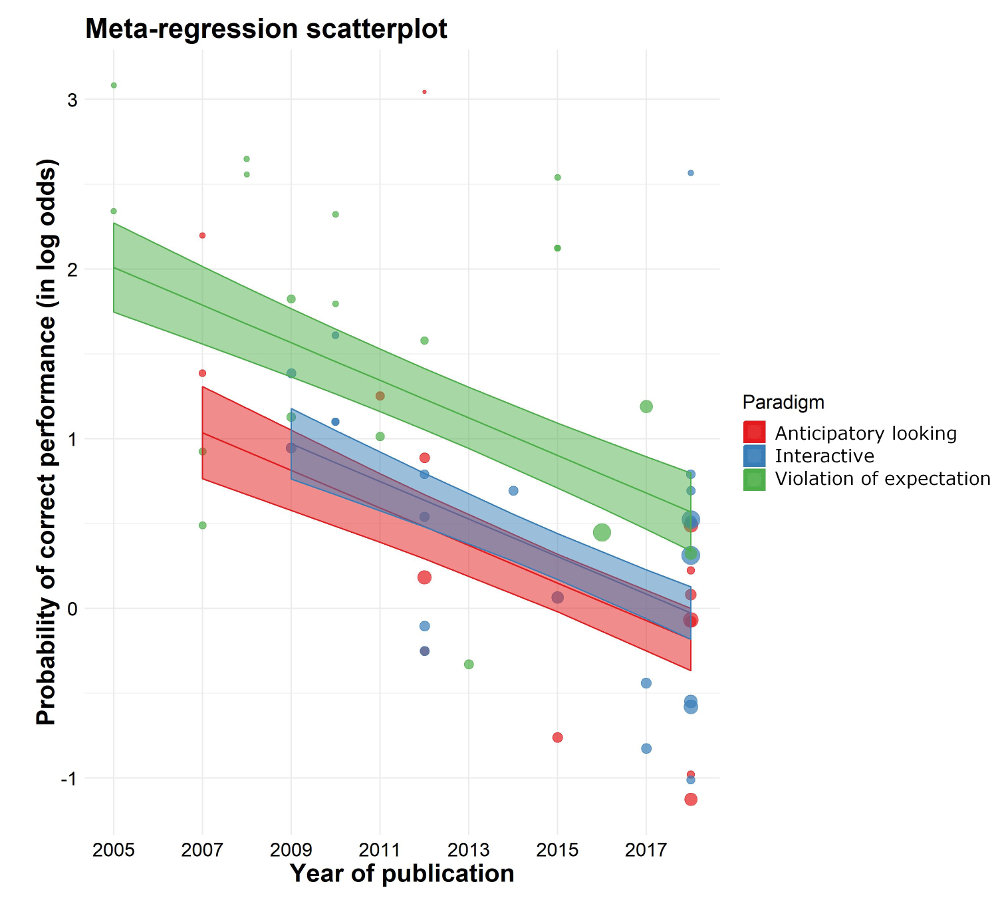

Finally, we found a very curious result: The more recent the study was, the less likely it was of finding that infants pass the task (Figure 1). Obviously, it is not to be expected that the successive generations of infants are getting worse in recognizing others’ false beliefs, so this finding might address some issues related to the studies themselves. In general, recent studies have bigger samples and better control conditions, which might have helped to reduce the biases of the initial studies. At the same time, it is likely that many articles reporting negative results could not be published until recently.

Figure 1.- Meta-regression scatterplot of correct performance in the non-verbal false belief tasks (measured in log odds; that is, the ratio between the probability of passing the task and the probability of not passing it, logarithmically transformed) as a function of the year of publication. The tasks are grouped according to the paradigm employed (anticipatory looking, interactive or violation-of-expectation paradigms). Each circle represents one false belief condition and its size varies depending on the sample size. Adapted from Barone et al. (2019).

This meta-analysis has been the first one in proposing an integrative view of all published non-verbal false belief tasks in children younger than 2 years of age. Infancy is a key developmental period in which implicit methodologies are used to test the origins of many psychological constructs, such as theory of mind and the specific capacity to attribute false beliefs. The emerging picture, however, is complex and questions the robustness of early false belief attribution. On the one hand, the effects tend to be statistically significant but, on the other hand, there are signs of publication biases that reduce our trust in such effects. In sum, the data agree with the possibility that infants are sensitive to other person’s mental states before developing a full-blown theory of mind by the age of 4. However, the different non-verbal tasks used to evaluate false belief attribution seem to rely on infants’ capacity to detect simpler mental states, like intentions and states of seeing and not seeing. Then, developing a theory of mind might be a gradual process that starts in a non-intellectualized, non-theoretical manner, from an intuitive sensitivity to others’ intentions (what is that person going to do?) to the ability to develop complex explanations of the others’ behaviors (how does this person represent the reality in order to act that way?).

References

Barone, P., Corradi, G., & Gomila, A. (2019). Infants’ performance in spontaneous-response false belief tasks: A review and meta-analysis. Infant Behavior and Development, 57, 101350.

Baron-Cohen, S., Leslie, A. M., & Frith, U. (1985). Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind”? Cognition, 21, 37–46.

Kulke, L., & Rakoczy, H. (2018). Implicit Theory of Mind – An overview of current replications and non-replications. Data in Brief, 16, 101–104.

Premack, D., & Woodruff, G. (1978). Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1, 515–526.

Scott, R. M., & Baillargeon, R. (2017). Early false-belief understanding. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21, 237-249.

Wellman, H. M., Cross, D., & Watson, J. (2001). Meta analysis of theory of mind development: The truth about false belief. Child Development, 72, 655–684.

Manuscript received on January 3rd, 2020.

Accepted on March 16th, 2020.

This is the English version of

Barone, P., Corradi, G., y Gomila, A. (2020). ¿Tienen los niños pequeños teoría de la mente? Ciencia Cognitiva, 14:1, 19-22.